Chairman of Turkmen Initiative for Human Rights, an underground activist network that gathers independent and reliable information on the current state of human rights in Turkmenistan. He is also the editor of the website Chronicles of Turkmenistan, which disseminates the findings of the network to the international community.

Imprisoned in 2002 following a crackdown on opposition and civil society leaders, Tuhbatullin was forced upon his release to flee Turkmenistan for exile in Vienna, Austria, where he currently directs the operations of his network and website. The author of numerous reports commissioned by multilateral organizations, including the UN Human Rights Council, he is a leading figure in bringing the world’s attention to human rights violations in Turkmenistan.

Tuhbatullin is a Reagan Fascell Democracy Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy from March 2010 to July 2010. During his fellowship, Tuhbatullin is examining how exiled activists can influence the politics of closed regimes, using the experience of Turkmenistan as his primary case study.

“I Had to Swear on the Ruhnama”

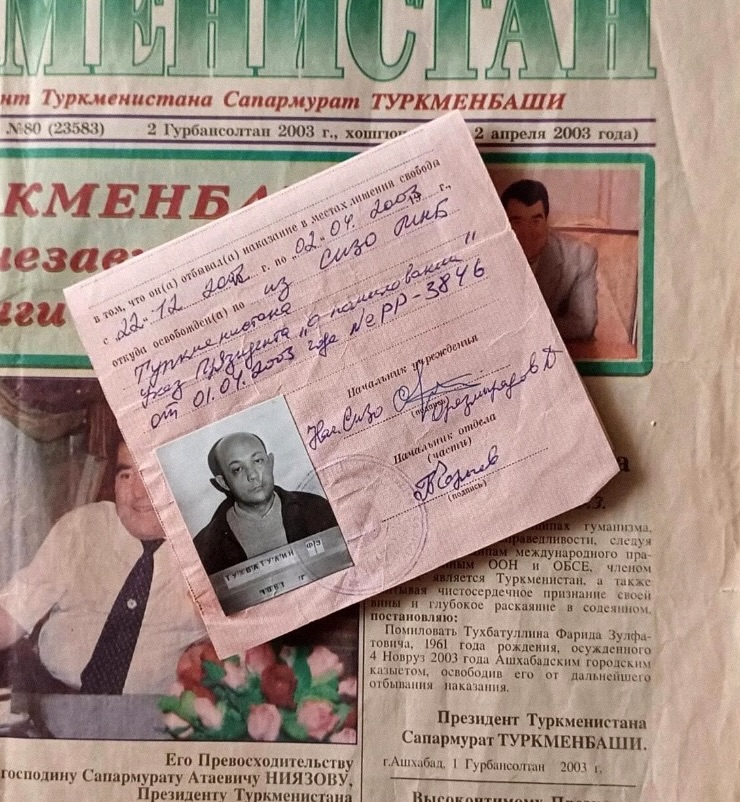

Human rights activist Farid Tuhbatullin learned about his release from the Ashgabat prison thanks to his cellmate’s radio. The cellmate, General Kabulov, had once overseen this detention facility, and out of respect, the staff had allowed him to keep a radio in his cell.

Before that, there was an accusation of plotting to assassinate the president of Turkmenistan — a conspiracy allegedly discussed with his participation at a conference of the International Helsinki Federation, then followed surveillance by security services, escape, an assassination attempt, protection by a special forces unit — and endless work: painstakingly gathering information about repression at home, piece by piece, and trying to draw the attention of weary international organizations to Turkmenistan.

Farid Tuhbatullin was lucky: unlike others arrested in the assassination attempt case against Turkmenbashi, he came out of prison alive.

There are places on the world map that humanity has all but forgotten — closed-off, dangerous countries where something terrible is happening. People disappear without a trace there, and getting in is difficult. Not that there’s any reason to go.

These countries are, in people’s minds, already ringed with barbed wire. Human rights defenders and journalists aren’t allowed in. It’s impossible to count the number of political prisoners — and even if it were possible, there’s no one there to do it. The best insight into what’s happening inside these sealed-off dictatorships comes from the stories of people who have lived and worked there, tried to change things, ended up in prison, and then, of course, fled.

Farid Tuhbatullin first landed in prison on charges of plotting against President Niyazov, then went into exile, and later lived under the protection of an Austrian special police unit because of death threats.

Turkmenbashi and Little Vera

When perestroika began, along with the loud exposés of the party leaders in the Central Asian republics, people in Turkmenistan also believed that change was irreversible and that freedom was about to arrive everywhere.

“The Cotton Affair,” “Adylovshchina” — these were perestroika-era phrases known to everyone. Newspapers finally began to write about how, for all those years, Central Asian republics had essentially been living under feudalism. Everyone was forced to pick cotton — the sick, the pregnant, the disabled, and the elderly alike. If you wanted to survive, you went.

In the Turkmen SSR (Soviet Socialist Republic), cotton feudalism never reached the extremes seen in Uzbekistan, and the republic escaped with just a few token dismissals. Two regional party secretaries were removed from their posts, including in the Tashauz region (now Dashoguz velayat), where Farid Tuhbatullin lived.

“In our region, they removed the first secretary and the second,” Farid recalls. “The second one was always, by tradition, some Russian uncle, an outsider — that’s how it was in all the Asian republics. They turned his official residence into a kindergarten. And that was the end of it. Perhaps the violations here weren’t as severe as in Uzbekistan, or perhaps the investigators never got around to us — either way, Turkmenistan escaped with little more than a slap on the wrist. It’s also possible that Moscow at some point realized that if they kept digging, they’d have to imprison everyone — and not only in Central Asia.”

Farid is a mechanical engineer specializing in land reclamation. During perestroika, he worked in the Ministry of Water Resources system and moved in educated circles. So when the referendum on preserving the USSR came, he voted “no”: he believed that Turkmenistan had not only enough natural wealth but also enough human resources to build a prosperous, independent country with a standard of living comparable to Kuwait’s.

In the beginning, it seemed like anything was possible. Young, educated Turkmen were riding a wave of cautious euphoria. Saparmurat Niyazov had gone from being the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Turkmen SSR to the president of an independent nation. But he hadn’t yet littered the country with golden statues of himself.

The first warning sign came from a completely apolitical direction.

“They were supposed to show Little Vera — a symbol of perestroika-era cinema — on central television broadcast from Moscow. But Niyazov went on air and said that Turkmen would not be watching such a thing. During the broadcast, Turkmenistan’s TV signal was cut off without warning. And after that, everything started rolling downhill very quickly. But at the time, the scale of the tragedy was impossible to imagine.

“You see, back in Soviet times, they drilled into our heads that Turkmen were wild and uneducated. Maybe there was some truth to that. But we had a military democracy — we elected our commanders, and if one failed to meet expectations, we replaced him. When Russia came to colonize the Turkmen — first as an empire, then as a Bolshevik state — its primary goal was to make sure we understood one thing: the leader is singular and untouchable, and no one may ever doubt him.

“In countries colonized by, say, Great Britain, people were taught to obey the law. In countries colonized by Russia, people were taught to obey orders. We’re still paying the price for that today.”

The Seal, Split in Two

Still, it would take some time before the consequences became clear. Turkmen were, for the moment, riding a wave of euphoria over the promise of change and reform. In the early 1990s, Farid Tuhbatullin stepped downfrom the Ministry of Water Resources to launch the Dashoguz Ecological Club, a community-based environmental group. The north of Turkmenistan lay within an environmental crisis zone caused by the shrinking of the Aral Sea, once the fourth-largest lake in the world.

The Turkmen Ministry of Justice officially registered the group, and for the first few years, Farid and other environmentalists were able to work without interference. They attended conferences in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Russia. But soon, all Turkmen civic activists began to feel the tightening grip of state control.

“Maybe I should have kept my head down and tried to ride it out,” Farid says. “But then I had this crazy idea — we started publishing a printed bulletin. There was no digital technology back then; we just printed small booklets about environmental issues.”

At the time, there was a fuel crisis — gasoline had vanished from filling stations. Those working at gas stations would siphon fuel off to their homes or relatives’ houses, selling it later for a hefty markup. Nearly every house on a street close to Farid’s home had become a makeshift gas station. The signal was simple: if an empty canister stood out front, it meant fuel was for sale. And the storage conditions? Dangerous beyond imagination. If one place caught fire, the entire street would be in flames within seconds.

Farid wrote an article about it for the bulletin. Not long after, he found himself summoned to meet with the head of the city branch of the KNB (National Security Committee). Farid suspects the official was protecting the illegal trade. The chief warned that he would shut down the organization.

I told him, “Here’s the imprint from our bulletin, here’s our registration certificate. You can’t shut us down — only a court can do that.”

But instead, they took him to the police department — straight to the office responsible for destroying seals. There, they took the official stamp of the organization and split it into two. “That’s it,” they said.

Farid went to the capital, knocking on every possible door. One of those was the OSCE mission, headed at the time by Romanian diplomat Paraschiva Badescu. She told him he should speak at the OSCE Economic Forum in Prague, and she arranged the trip for him and two other activists.

In Prague, Farid Tuhbatullin met Batyr Berdyev, Turkmenistan’s representative to the OSCE, who also served as the country’s ambassador to Austria. “We got along well,” Farid later recalled. “The ambassador even invited me to lunch.”

Two years later, the two men would find themselves in the same prison, accused of conspiring to assassinate Turkmenbashi. Berdyev was sentenced to 25 years. No one would hear from him again; human rights defenders would later recognize him as a victim of enforced disappearance.

Before the trial and sentencing, though, Farid and Batyr would cross paths one last time in a prison corridor — one being led to interrogation, the other back to his cell.

After returning from Prague, Tuhbatullin was summoned by the Minister of Justice. It was clear the authorities had not yet decided what to do with the environmentalist, and they were operating in “preventive mode.”

The minister asked why the Ecological Club’s bulletins contained no references to Turkmenbashi’s works or quotations. “Because,” Farid replied, “the president has never spoken on environmental issues.” The minister pressed further: why, in children’s booklets about local wildlife, were there no quotes from Turkmenbashi? “Because,” Farid said, “he’s never said anything about animals either.”In the end, Farid was let go without incident — and the authorities even restored the club’s official seal. The Dashoguz Ecological Club was once again legal, just as before.

“How Many Pages of the Ruhnama Has Gulshirin Read?”

By then, Farid was no longer the same as before. He had realized that all it took was the whim of an official — whether a minister or the head of the city branch of the KNB — and both the organization and its members could be wiped out overnight. He began studying human rights, determined to be ready for any situation in a country rapidly sliding back into a medieval-style dictatorship.

He attended a human rights school in Poland. “It was an incredibly valuable program,” he recalls. “I learned a lot of important things there.”

“I got my visa in Moscow,” Farid says. “Back in 1993, at the CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) summit in Ashgabat, Yeltsin and Niyazov signed an agreement on dual citizenship. After the signing, Niyazov ceremonially handed Yeltsin a green Turkmen passport. Anyone born in Russia or of ethnic Russian descent was eligible to apply for Russian citizenship. My wife was born in the RSFSR (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic), so she qualified and got hers. I received mine later, through family reunification. With Turkmenistan enforcing visa requirements for every country on the map — including its fellow CIS states — a Russian passport became a much-needed ticket to easier travel. I would go to Moscow, get my visa there, and then head to Europe from the Russian capital.”

In the early years, Farid says, even within the security services, there were still perfectly reasonable people who genuinely didn’t understand what 85non-governmental organizations were or how they operated. After his trip to the human rights school in Poland, instead of being summoned to the security office, he was invited to a café. There, they asked him to explain what these “NGOs” were all about.

There seemed to be no hostility — just genuine curiosity and an attempt to understand whether such groups could pose a threat to Turkmenistan’s security, or perhaps have no impact at all. Or maybe it was simply one of the security services’ familiar games: “We’re not your enemies — just help us understand how this works.” According to Farid, such games were played by the security services in nearly every post-Soviet country.

At the end of 2002, after another trip to Europe, Farid Tuhbatullin stayed in Russia for a couple of extra days — he’d been invited to speak at a conference near Moscow titled Human Rights and Security Issues in Turkmenistan, organized by Memorial and the International Helsinki Federation. Farid was the only speaker from Turkmenistan who still lived there. The others — human rights advocates from international organizations — would return home after the conference, not fly back to Turkmenistan. But Farid was going back.

“After I got home to Dashoguz, I was immediately summoned to the KNB office — by then it had already been renamed the MNB, the Ministry of National Security,” Farid recalls. “The chief told me I’d have to go to Ashgabat to give testimony, and then I’d be allowed to return. They drove me home so I could grab my passport. I left a note so that if I didn’t come back, my relatives would know where to look for me. Then they took me to the local airport. Ours is a small town — I wasn’t in handcuffs, but everyone knows each other, and word gets around fast. I could already see people avoiding me. On the plane, one of my escorts sat next to me and immediately launched into a speech about what an incredible karate and martial arts master he was — apparently to make sure I didn’t even think about trying to escape. As if there’s anywhere to run on a plane.”

By then, Farid suspected he wasn’t just being taken to “give testimony.” He was only glad that a year earlier, he’d sent his family to Russia. In Ufa, they had relatives who owned a small vacant apartment. Farid had determined that his children wouldn’t have to finish school in Turkmenistan, where Ruhnama, the “great and all-encompassing” work of Turkmenbashi, formed the core of every subject.

He often described how that worked. For example, a math textbook problem might read: “On the first day, the girl Gulshirin read 15 pages of the Ruhnama. On the second day, she read 17 pages, and on the third day, 22 pages. How many pages of the Ruhnama did Gulshirin read in three days?”

Goat Paths from Uzbekistan and Generals in a Cell

In Ashgabat, where the security services had told Farid he was only expected to give some official testimony and then return home, he was sent straight to a detention facility. At first, he thought it might be some intimidation tactic — a campaign to crush NGOs. Detain a few people, and the rest will self-censor, lying low for years, if not forever. Farid didn’t yet know that in that very prison and in the National Security offices, volumes of criminal case files were swelling before his eyes — files accusing people of an anti-state conspiracy and plotting to assassinate the dictator.

“In the cell I was put into, there was just one other person,” Farid recalls. “By the standard logic of Soviet-era detective stories, I immediately assumed he was planted — there to provoke me into confessing to something unknown or just to make my life unbearable. Can you imagine? It turned out this was the very man who had secretly smuggled Boris Shikhmuradov back into Turkmenistan!”

Boris Shikhmuradov had served as Turkmenistan’s foreign minister and later as its ambassador to China. In November 2001, he publicly declared his turn to open opposition, forming the People’s Democratic Movement of Turkmenistan and launching the opposition website Gundogar. Nobody knew that after making a high-profile statement abroad and failing to return to Ashgabat, Shikhmuradov had secretly re-entered Turkmenistan.

On November 25, 2002, Turkmen state media (the only media there was) reported an assassination attempt on President Saparmurat Niyazov. A KAMAZ truck had driven toward the presidential motorcade and opened fire. As the Prosecutor General of Turkmenistan, Kurbanbibi Atadjanova, later told a government session: “The enemy’s bullet did not reach our beloved Serdar, the Great Saparmurat Turkmenbashi. The Almighty protected him from the treacherous shot and preserved him for us.” (Atadjanova herself would be arrested for corruption in 2006 and sent to Farid’s hometown of Dashoguz, to a women’s prison.)

Niyazov blamed the assassination attempt, as dictators often do, on “fugitives.” In addition to Shikhmuradov, the other accused included former Ambassador to Turkey Nurmukhamed Khanamov, former Deputy Minister of Agriculture Saparmurat Yklymov, and former Central Bank head Khudaiberdy Orazov — all of whom were residing abroad. Meanwhile, in Turkmenistan, the authorities began arresting anyone already “on the radar” of the security services. Among them was Farid Tuhbatullin.

“My cellmate Davlet used to be the head of an oil depot in a border district with Uzbekistan,” Farid recalls. “Back then, we had a practice of bartering goods with Uzbekistan. Niyazov would set a cotton collection quota — completely impossible to achieve for obvious reasons — and our officials would strike a deal with the Uzbeks: we’ll give you diesel or gasoline, and you give us cotton. The oil depot chief himself was the one in charge of transporting the fuel. He knew all the backroads and secret paths.

The officials arranging the exchanges didn’t want to involve the border guards because they were part of the National Security Ministry. And so, using these secret paths, my cellmate brought Boris Shikhmuradov into Turkmenistan from Uzbekistan. Later, they put Yklym Yklymov — the brother of Saparmurat Yklymov — into our cell as well.

Their cell had previously been just a storage room: it had a barred window but no glass, and no bunks or beds — detainees were brought in with whatever they had. I assume the other cells were already overflowing with people accused of the assassination attempt on Niyazov. Yklym Yklymov — who had secretly hosted Shikhmuradov at his home — had been severely beaten. Davlet and I weren’t beaten; we were arrested later. Those who were taken on November 25 were beaten badly. Later, I would share a cell with another young detainee, a kid who didn’t understand what he was accused of. They electrocuted him and tortured him with the “elephant” method — the “elephant” being a torture technique where a gas mask is placed on the victim and the hose is clamped, cutting off the air supply.

The charge against me was that I knew about an alleged assassination plot against Saparmurat Niyazov, supposedly discussed at a human rights conference near Moscow, and did not report it to the security services. But, as I later explained, the conference was organized by a completely different opposition group — the United Opposition of Turkmenistan, led by Avdy Kuliev. So even if I had wanted to cooperate with the investigators, I had nothing to tell them.

“Later, I shared a cell with the head of the international protocol service — a good guy, from my region. He knew my father well; back in the day, my dad had been the chief physician at the polyclinic of the Fourth Department of the Ministry of Health, treating the ‘big shots.’ Then they transferred me to a cell with General Kabulov, the first commander of Turkmenistan’s border troops. He was also a very good, polite man — always addressed me formally.

“Then, as the trial approached, I realized my entire criminal case boiled down to a failure to report — a maximum of three years, which seemed light.

So they decided to ‘add’ illegal border crossing. The thing is, our Dashoguz region and Uzbekistan’s Khorezm region had a sort of minor border-movement arrangement: we could visit for three days without a visa, and vice versa. Border guards would not only stamp passports but also record the visit in a logbook. Once, returning from such a short trip, a young border guard forgot to log me. As a result, they told me I had crossed the border illegally. The passport stamp didn’t matter — the logbook entry was the official record, and it was missing.”

“Me and My Fellow ‘Terrorists’”

The trial was swift. Not a single defense witness was allowed, even though participants of that conference near Moscow — members of Memorial and the International Helsinki Federation — wanted to come and testify, to confirm that no one had ever discussed assassinating the president of Turkmenistan at any session. Their letters to the court, of course, went unanswered.

In court, Farid asked, “At least bring some prosecution witnesses! Let someone say that I, for example, was present during a conversation about assassination plans or that I crossed the border illegally.” The reply was always the same: no need, the court understands everything.

During a recess, his lawyer whispered that an OSCE official had visited Niyazov, and there might be a chance to get a suspended sentence and leave the courtroom if Farid pleaded guilty. He didn’t. He was sentenced to three years in prison. Compared to the 15–25-year sentences the other defendants received, it seemed relatively light.

What torture Boris Shikhmuradov endured remains unknown. He was arrested on December 25, 2002, and just three days later, his sentence was announced: first 25 years, then, only a few hours later, life imprisonment.

The sentence was rewritten at Niyazov’s request. Since then, no one has heard anything about Shikhmuradov. Interestingly, two years later, a book allegedly authored by Shikhmuradov appeared briefly on the shelves of Turkmen bookstores: “Me and My Fellow Terrorists.” Human rights defenders around the world launched the 2013 campaign “Show Them Alive!” demanding proof that political prisoners who disappeared from jails were still alive. But nobody showed them alive — or dead.

“After the verdict, my lawyer said we had ten days to file an appeal,” Farid recalls. “He came to see me in detention several times, but we weren’t allowed to work on the appeal. The days were slipping away, and time was almost up. So I wrote the appeal myself on a piece of paper and handed it to a guard.

“After that, the prison warden called me in, offered me tea and coffee, and said: ‘Why bother with these appeals? Better write a full confession, and things will go easier for you. Otherwise, they’ll send you away on a transfer, and we won’t be responsible for what happens to you. Who knows what they’ll do to you? And don’t think you’ll be out in three years — they will find another charge.’”

Farid refused. He asked that the cassation appeal he had written be sent as required. Just in case, he packed his things in the cell, expecting a transfer. A week later, he was summoned to the investigator. Farid even remembered the investigator’s last name: Khizhuk. He took out a sheet of paper from a typewriter with a pre-written full confession of guilt. He said that Farid had to copy it by hand, word for word. Moreover, he added, “I didn’t come up with or write this; it was sent to us from the President’s administration. The decision has already been made. You sign it today — you’ll be free tomorrow.”

Farid asked for a day to think it over. He returned to his cell and told everything to his cellmate — at that time, he was sharing the cell with General AkmuradKabulov, the former head of Turkmenistan’s State Border Service. Before leading the Border Service, Kabulov had served as the first deputy head of the KNB, giving him an intimate knowledge of the inner workings of the security apparatus. The general said, “Don’t even think about it — sign it. Who benefits if you stay behind bars? Your family? And what will happen to them, the relatives of an enemy of the people, have you thought about that?”

Farid didn’t sleep all night. In the morning, he was summoned again. He painstakingly transcribed by hand the confession that had been carefully prepared for him the day before, then returned to his cell. There were no radios in the detention center except for Kabulov’s. When he had served as first deputy head of the KNB, Kabulov had overseen this very detention facility. So he was guarded by his former staff. And indeed, Kabulov’s radio worked — though it only picked up Ashgabat broadcasts, even that was important.

One evening, Farid heard a broadcast announcing his pardon. The message stated that he had been released and was already at home. The next morning, he was summoned with his belongings, forced to swear on the Ruhnama, and sign documents committing not to meet with foreigners, not to break the law, not to go, and especially not to travel without the permission of a security officer. Farid was ordered to return to Dashoguz.

“Remember, your parents and brothers are hostages.”

In June 2003, Turkmenistan unilaterally ended its dual-citizenship agreement with Russia. The government gave the country’s citizens two months to choose: either renounce their Turkmen citizenship and move to Russia, or forfeit their Russian citizenship and stay in Turkmenistan.

Farid called the officer assigned to oversee the process and asked whether he would be allowed to leave the country if he renounced his Turkmen citizenship. His family was in Russia, travel was prohibited, and he couldn’t see his loved ones — so renouncing citizenship seemed the simpler option.

The officer wasn’t prepared for the question and promised to consult his superiors. A few days later, the officer called back and said, “We’re willing to let you go to Russia to see your wife and children for ten days, no more. But remember — your parents and brothers are hostages. They stay here. Think of them and don’t do anything foolish.”

My father then told me, “Don’t come back. They won’t harm us, but your life won’t be safe here. You’re the head of the family — think of your children, think of what you can do for your country if you stay where you can speak freely.”

I went to my family, who were in Ufa, and received an invitation from the OSCE to come to Vienna and speak. The OSCE had advocated strongly on my behalf while I was in prison. In Vienna, a major conference on the human dimension was taking place, and as part of it, I gave a small briefing to a group of diplomats. I spoke about what was happening in the prisons, about how prisoners were tortured, and about how hundreds were arrested allegedly for plotting against Niyazov. Afterwards, two Austrians approached me and said that an employee of the Turkmen embassy had been present in the room where the briefing took place and would report everything to Ashgabat. “You must not return,” they said. “It’s better to apply for asylum. If you go back to your homeland, we won’t be able to get you out of prison a second time.” And I made my decision. Two months later, I was granted refugee status.

When Farid was arrested, his brother, the deputy military commissar of the city, was immediately fired. His father was also “asked” to leave his job; he had already retired from his position as chief physician of a clinic, but continued working as a radiologist. There was, in a sense, “nowhere left” to exact revenge on the family. True, they still smashed windows at the house and staged petty provocations, but primarily out of inertia. Farid Tuhbatullin exhaled and lowered his defenses. That was a mistake.

In 2010, he was approached by officers from “Cobra,” an Austrian Federal Ministry of the Interior counterterrorism unit created after the 1972 Munich Olympics attack. They warned Farid that an assassination attempt was being prepared against him and placed him under protection. The neighbors grew frightened — to them, the permanent police post outside his home was a sign of danger. Eventually, Farid asked for the protection to be withdrawn.

Instead, he was given several security lessons: for example, never sit by a window when entering a café, and in any location, quickly identify areas within a line of fire. In short, after these sessions, Farid felt more afraid than he had upon first hearing of the planned attack.

Now he knows for sure: you can never relax, no matter how many years have passed. Dictatorships have long memories, and counting on “time will pass — they’ll forget” is both foolish and dangerous. I have heard of assassination attempts against human rights defenders and journalists from Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan, even after they had seemingly been living safely in other countries. Vigilance, caution, and distrust — as grim as it sounds — are essential for survival anywhere if the dictatorship you escaped has marked you as an enemy.

In Austria, immediately after receiving asylum, Farid registered the NGO Turkmen Initiative for Human Rights. He collects information on human rights violations and writes reports for international organizations. He also runs the website Chronicles of Turkmenistan. It is not hard to guess that Tuhbatullin has plenty of work. But the most challenging part is not systematizing, not compiling reports, not knocking on every door to urge attention to the situation in Turkmenistan — it is obtaining information from a country where any contact with a foreigner or an “enemy of the people” in exile can land someone in prison for a long time, and possibly make them disappear there altogether.

The exact number of political prisoners in Turkmenistan’s prisons isunknown. No such statistics exist. Likewise, the number of those who have died or been killed is unknown: the Show Them Alive initiative lists as victims of enforced disappearances those prisoners with whom there has been no contact for years or even decades. Human rights defenders have documented 162 such cases. Sometimes a person turns out to be alive: for example, the opposition figure Gulgeldy Annaniyazov, who had been included on the list, was found to be alive. He was arrested in 2008 and sentenced to 11 years in prison, allegedly for illegally crossing the border.

He served his entire term in solitary confinement under incommunicado conditions. When his term ended, the authorities added another five years in a penal settlement for Annaniyazov, and only then did people learn that he was alive.

Incidentally, before his arrest, Annaniyazov lived in Norway, where he had political asylum. He returned to Turkmenistan in 2008, when, after Niyazov’s death, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov came to power — he believed in the end of dictatorship and the coming changes. From time to time, officials from the Turkmenistan embassy in Austria also approach Farid Tuhbatullin and offer him to return: “If you come, you’ll see your family, and no one will touch you,” they say.

Farid will not go.

(Stories from the book “Fighting for Freedom in the World” – Author: Iryna Khalip)

“These heroes have taught and inspired me beyond words. Their greatest lesson is simple yet profound: continue doing what you do, no matter how horrific the circumstances. We are stronger than dictatorship. Love, Iryna.”